In the world of data, big data often gets the hype.

And with good reason: many of the transformative models that are having a significant impact across industries are trained on massive amounts of data- whether public or private.

However, small datasets can be just as fascinating and, in many ways, more challenging. You can’t always take the easy way out by saying, “We need more data!” What if the data is private, expensive, or you’re working on a shoestring budget? In such cases, you have to extract blood from a stone, so to speak.

In fact, as you gain more experience and become familiar with various techniques, you may realize that you didn’t need as much data as you initially thought!

Definition of Small Data

As far as I’m aware, there is no strict definition of what constitutes “small data.” However, the techniques I will discuss in this article may be relevant in the following scenarios:

- The number of observations is less than 100: Many data scientists won’t even approach a dataset with fewer than 100 observations, but you’d be surprised at what is sometimes possible.

- P > n (i.e., the input dimensionality is larger than the number of observations): Working in this scenario requires specialized techniques to avoid overfitting and extract meaningful patterns.

- Certain industries are more likely to encounter small data: Fields where collecting data is difficult or expensive—such as medicine, sociology, economics, or marketing—often deal with small datasets. I’ve personally had significant experience in two of these fields, where datasets with fewer than 100 observations are common.

- A high premium on explainability: When explainability is critical, different techniques are needed compared to those used in purely predictive models.

- Low signal but high noise: If you have a low-signal, high-noise dataset, these techniques may also prove useful.

General Ideas

There are several general tips and tricks that can be effective when handling small data. Let’s explore them one by one.

Modeling: Start Small, Simple, and Solid

The first tip is more of a philosophical modeling choice, but it has served me well. When handling small data, it is advisable to start with a small, simple model and progressively increase its complexity as needed.

What does this mean in practice? A good rule of thumb is to use a maximum of one feature for every ten observations. For example, if you have 100 observations, begin with fewer than 10 well-constructed features. Validate your model against a benchmark before expanding further.

This cautious approach mitigates the risk of overfitting and fosters a better understanding of the underlying data.

In contrast, when working with very large datasets, it is often possible, and even preferable, to begin with a large and complex model. This approach allows for the capture of intricate patterns while using techniques such as regularization and cross-validation to avoid overfitting. This is especially true in deep learning contexts, such as large language models (LLMs) and other generative models.

For machine learning engineers focused on scalability, the advice to “start small” might seem counterintuitive. Why not let the model learn the features on its own? The answer lies in efficiency: when the dataset is small, this type of feature learning is inefficient. It is far better to encode your domain knowledge, starting with a very simple, functional base model, and then gradually building on it.

Handcraft Features: Channel the Craftsperson

The importance of understanding the domain in the context of modeling depends heavily on the size of the dataset. For small datasets, domain knowledge becomes crucial. With limited data, there often isn’t enough coverage of potential variations. As a result, feature engineering plays a vital role in encoding prior information and domain expertise directly into the model.

In contrast, when working with large datasets, models can often learn patterns on their own, reducing the reliance on extensive domain knowledge. In fact, inserting domain knowledge into these models can sometimes be clumsy or unnecessary, as they can inherently discover patterns through training.

To illustrate, consider the case of time series forecasting with limited historical data or context. Domain knowledge enables the forecaster to make informed assumptions about the data-generating process, leading to better decompositions and more effective modeling choices. This “handcrafted” approach results in sparser models with fewer assumptions, which can often yield superior results in these scenarios.

However, when dealing with large-scale time series datasets, deep learning models such as Transformers are increasingly outperforming handcrafted methods. With vast amounts of data, these models are capable of capturing intricate patterns and relationships without relying heavily on pre-engineered features.

Less Focus on Hyperparameters

This idea may be controversial within the machine learning community, but it reflects my experience. At small scales, the choice of model architecture and hyperparameters often doesn’t make a significant difference.

With effective feature engineering, you’re likely to achieve excellent results as long as you take care to satisfy the basic assumptions of your chosen model. Whether you’re using XGBoost, CatBoost, LightGBM, TabNet, or even vanilla linear regression, the results will typically fall within a few percentage points of error. At least, that has been my experience.

I believe many people mistakenly spend too much time on hyperparameter tuning when working with small datasets. This time would often be better spent on feature engineering or consulting domain experts to enhance the quality of input data.

In contrast, when scaling up to large datasets, architecture choices and hyperparameter tuning become much more impactful. Optimizing model architectures and fine-tuning hyperparameters can lead to significant performance improvements in such cases.

Performance Should Be Accompanied by Explainability

In situations where data is limited, model explainability becomes critical. Understanding how and why a model makes its predictions is essential for building trust and identifying potential issues. When you have only a small holdout set for validation, it’s even more important to demonstrate that your model is based on a logical and robust foundation.

With large datasets, performance often takes precedence. In such cases, you can rely more heavily on metrics as proof of success. Achieving high accuracy, predictive power, or increased revenue may be sufficient to convince stakeholders of the model’s validity.

Use Measures of Confidence

When dealing with small data, it’s wise to incorporate measures of confidence, such as confidence intervals or bootstrapping, to assess the reliability of your predictions. Additionally, strive to understand edge cases or scenarios where your model might fail when extrapolating beyond the available data.

Of course, even with large datasets, understanding the confidence of your predictions remains important. However, it becomes slightly less critical, as the dataset is often large enough to accurately reflect the true data distribution.

Encoding Prior Knowledge with Reasonable Assumptions

Lastly, when dealing with small data look to encode as much information as is reasonable using prior knowledge, similar datasets or transfer from other problems. This can be done through eg. Hierarchical Models, Bayesian Models, Embeddings, Transfer Learning, Self Supervised methods etc.

Practical Methods for Success with Small Data

Beyond the general strategies mentioned earlier, let’s explore some practical methods that are particularly helpful when modeling with small datasets.

Feature Selection

When the number of potential features significantly exceeds the number of observations, feature selection becomes a critical step. As mentioned earlier, a good rule of thumb is to aim for about 10 observations per feature. For example, a dataset with 100 training examples might work well with a model using 10 features. However, small datasets often come with hundreds or thousands of potential features, requiring careful curation.

To solve this problem you’ll have to undertake in some serious feature selection.

I like to start by asking domain experts. Many data scientists will shy away from this step and head straight to an algorithm selection. However, domain knowledge can guide your selection and help you to find the obvious relations in the dataset. I found this to be particularly true when working in the medical domain- doctors were always best placed to offer advice on what features should enter our algorithms. If we could provide a data driven perspective too, all the better.

Next, you’ll need to carefully consider the purpose of the model. Is it important to understand associations or causal structure? Is the purpose purely predictive performance? Do you need to explain why a model makes a certain decision? This will help to guide your selection. For example, if you need to explain why your model makes a certain decision, it may be necessary to include features that humans can understand, things like embeddings or dimensionality reduction might need to be dropped.

That said, below is a summary of the most common methods and associated advantages and disadvantages.

- Measures of Association: Measures such as Correlation, Mutual Information or Predictive Power Score analysis assess the relationship between your features and the target. These methods help to identify strong univariate relationships between the inputs and the target. Don’t put too much weight into these measures, however. The 1-to-1 nature of these measures means they often fail to select features that are important because they are obscured by interaction effects and other covariates.

- Domain Knowledge: As mentioned above, domain knowledge involves incorporating subject-specific expertise into the feature selection process. Domain experts can guide the selection of relevant features based on their understanding of the problem, potentially improving the model’s interpretability and performance. However, it’s important not to put too much blind faith in domain experts. Sometimes, you are there to disrupt the status quo and find something new. And occasionally, domain experts are plain wrong. Be humble and open to suggestions but also try to verify them with evidence.

- Built-in Mechanisms: Some machine learning models inherently include mechanisms for feature selection. Regularization techniques (e.g., L1 regularization) penalize the model for including unnecessary features, encouraging sparsity. Stochastic gates in neural networks and tree-based methods like decision trees can implicitly perform feature selection by giving more importance to informative features during training. The great thing about these methods, is that no additional selection processes are required, everything is taken care of. However, the lack of control and the implicit assumptions in the selection process can be a weakness.

- Wrapper Methods: Wrapper methods involve the calculating the model’s performance in evaluating feature subsets. Common filter methods such as simulated annealing and genetic algorithms, systematically explore different feature subsets to find the combination that optimizes the model’s performance. These methods are somewhat prone to overfitting but often provide excellent performance when using appropriate validation sets. In my experience, the automatic nature of these methods also lends itself to the inclusion of some rubbish features, which is a real drawback for models that require explainability.

- Bayesian Priors: Finally, Bayesian priors introduce a probabilistic framework for feature selection. The spike-and-slab prior, for instance, combines a spike in the centre with a dense ‘flat’ slab shape, allowing the model to effectively model the problem while thinning out unnecessary features. Another prior, the Laplace prior is equivalent to L1 regression.

Model Choice

When working with small data, it’s better to favour simpler models with fewer features, interactions and non-linearities. This goes hand in hand with my advice to start modelling small and build up as you go.

Supervised Learning

The following models are particularly useful as a starting point:

- Linear Models (all variants)

- Spline Models (e.g GAMs)

- Tree-based models (particularly simple decision trees or Random Forest models)

- Shallow NNETs

Linear models are always an excellent choice because of their simplicity and explainability. It’s very simple to start with a straightforward, underfit model and then add further complexity. Linear models are also suprisingly flexible. Consider the possible variations of the Generalized Linear Model that enable modelling of Gaussian problems, count data, binary data, classification problems, survival analysis etc etc. Not to mention extensions that use piecewise-linear basis functions or Fourier terms.

Spline Models are an excellent choice as an inherently non-linear model extension. Spline models eg. Generalized Additive Models (GAMs) consist of a combination of basis curves, normally natural cubic splines combined with some kind of penalty on the complexity. These models allow for modelling complex relationships while maintaining control and simplicity.

Other Methods

As well as the typical supervised methods, there are also situations where it is advisable to extract patterns from the structure of the data itself. Several methods can support in learning this structure without the need for explicit labels.

- Semi-supervised models

- Self-supervised methods

- Embeddings

Self-supervised methods are particularly useful in areas where you potentially have a lot of training data but very few labels. Algorithms such as Constrastive Predictive Coding help to learn the data structure by predicting future values in the latent space. Self-supervised learning has, for example, driven recent progress in domains related to audio analysis (speech recognition, music, audio classification etc).

Data Augmentation

Data augmentation is a strategy to bolster model performance and help promote generalization. Rather than relying solely on the original dataset, we can introduce variability by transforming the existing data. Common techniques include random rotations, flips, scaling, and warping, effectively expanding the dataset and enriching its diversity. A note of caution – I have found that data augmentation works best when you truly understand the underlying nature of the data generating process. If the transformations produce examples that are not likely to be seen in production then they might as well be useless.

Data Augmentation is however, often extremely beneficial in small data scenarios such as anomaly detection. Often, it’s not possible to gather labelled data for every possible anomaly and therefore, by augmenting the existing labelled data it’s possible to cover a lot of potential variations. The result is a more resilient model capable of delivering robust predictions when confronted with novel or unseen data.

Working with Small Data: Resampling & Validation

Finally, I would like to touch on some of the aspects of validating a small data model.

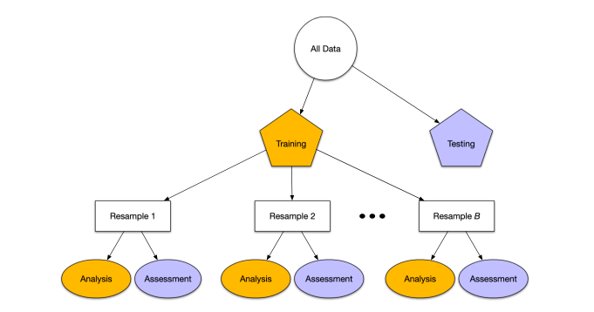

One key difficulty that you often encounter in such scenarios is that your training and test sets have different distributions. This means that performance estimates may vary considerably depending on the random sampling of these sets.

To mitigate this, it is often a good idea to resample the training and test sets, each time calculating the performance metrics. This will allow you to see the likely performance range in a true holdout set. Note - I recommend to use a fixed model and set of features for this process. This ensures that you do not overfit to every new training set sample.

I would also like to mention a particular approach that I have seen in industry and used personally. In many academic tutorials and courses, in the context of k-fold cross validation, people are often taught about the standard train/validation/test split. This is the standard method, perfectly applicable on data sets of a reasonable size.

On the other hand, if your data set very very small, you may want to avoid any resamples, validation and tuning. On small datasets, it’s completely possible and common to overfit the data, just by reusing the holdout and/or test sets. To get better generalization properties, do a single fold train/test split.

However, you should only look at the test set results once! Once you’ve peeked, you can’t now use the knowledge of your test set results to make changes, without potentially overfitting and risking a decrease in generalization performance.

This might seem counterintuitive, as it goes against the common wisdom. I only recommend this approach when the dataset is very limited- specifically, with fewer than 50 observations in total. If your holdout/test set contains 10–20 observations, be strict and use single-fold validation. No peeking!

Summary

In this article, I’ve explored the challenges and strategies for handling small datasets in Data Science and Machine Learning. I emphasize the importance of a thoughtful approach: start with simple models and gradually increase their complexity. Build a solid foundation for understanding the data, avoid overfitting, and ensure strong generalization, even when the data may not be highly representative.

Leverage domain knowledge by incorporating it into the model through feature engineering. Don’t hesitate to consult experts in your field for insights!

Lastly, I’ve shared practical techniques for small data modeling, such as model selection, feature engineering, data augmentation, and alternative validation methods.

I hope this article provides valuable insights to help you tackle your next small data project—so that next time, you won’t feel the need to throw your hands in the air and say, “We need more data!”

Leave a comment